Autocoder - Finetuning GPT-2 for Auto Code Completion

TL;DR. This link provides the code repository that contains two readily downloadable fine-tuned GPT-2 weights, a quick start guide of how to customize Autocoder, and a list of future pointers to this project. Although this blog looks like a technical introduction to Autocoder, I also by the way talk about a lot of relevant stuff, such as nice work, status quo, and future directions in NLP.

This blog introduces 🤖Autocoder - A basic and simple tool for code generation, built upon the pre-trained gpt-2 variants provided by HuggingFace’s 🤗transformers library. Below presents the workflow of Autocoder at training and inference time.

This blog first gives an introduction to the project’s background, and then reveals the details of how the dataset is prepared and the fine-tuning process is conducted in programming with Python. I will also give some of my personal reflections on the generated codes by Autocoder. Finally, a list of future pointers to Autocoder will be presented. The outline of this blog is organized as follows.

1. Background

Autocoder is designed for the code completion task (CCT) where a sequence of codes written by the programmer 👨💻 are detected as the context to prompt the automatic generation of the uncompleted codes by a program 🤖. Currently, many IDEs are able to auto-complete code but in a limited way. That says they only perform well in completing short sequence of codes in situations where the generated codes do not so heavily depend on the context of long sequence, such as, in PyCharm, completing a method’s name, variable’s name, etc. When there is a bottleneck, people try hard to escape from it although it is usually hard. Facing this bottleneck, now it makes sense to think about if the CCT can be advanced by taking a further step, namely, taking longer context into account for generating useable code in more complicated situations.

Based on the current progress of deep learning, the answer is yes but in a semi-automatic way. It is likely to train a deep model big enough to memorize or summarize rules or patterns of statistically commonly-used codes by the real programmers. For example, in Figure 1, the factorial code snippet is generated correctly basically because the model learns from the training codes that most programmers have written it in this way. However, for situations where the code required for generation is unusual such as changing n to another name, it is easy to fool the model to generate some unexpected codes(will talk more about this in Section 4).

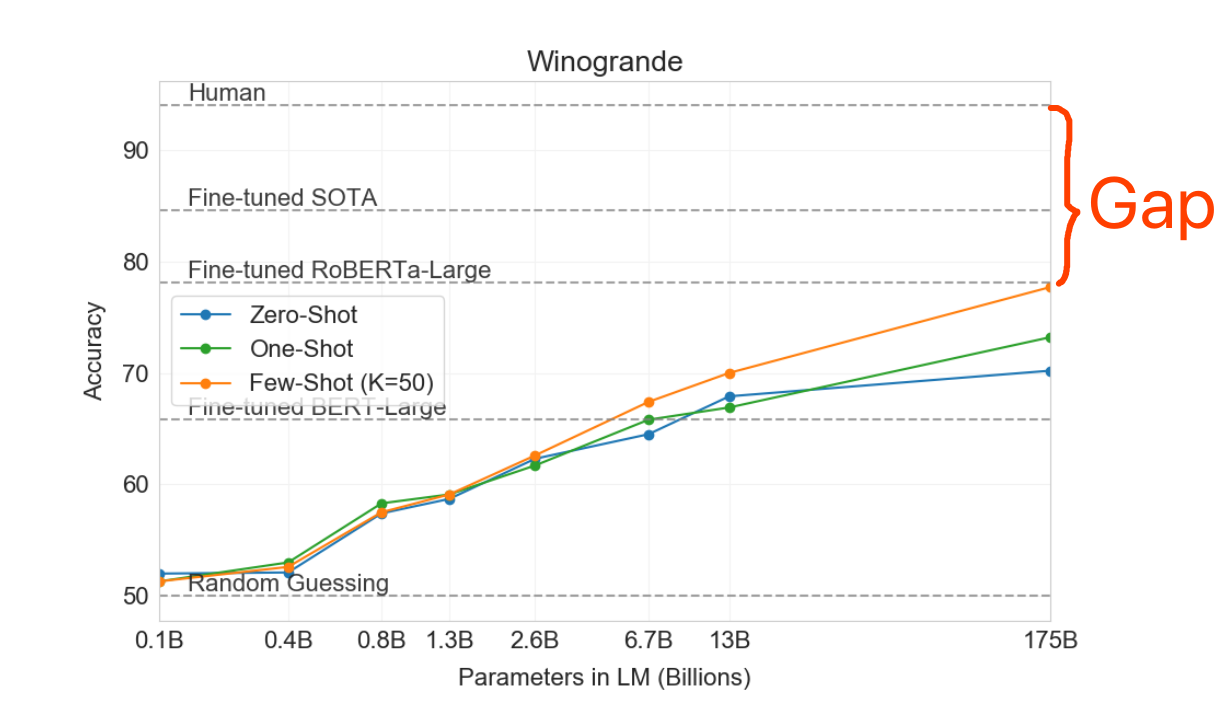

This reflects an important weakness of the trained model - the lack of reasoning, which has raised much concern in the deep learning community over the last few years. For knowing about the concern, it is recommended to read the book of why or the Chinese Room Experiment. To gain a general sense of how far nowadays the deep models are from reasoning, the following graph from the GPT-3 paper (Brown et al., 2020) tells something. I annotated the gap indicating the difference between human’s performance and machine’s (a very big model with 178B params) performance in the Winogrande task (Sakaguchi et al., 2019) in few-shot setting (making predictions with only few examples fed to train the model).

Hence, given the lack of reasoning, the codes need to be tweaked by humans if they are generated in an unexpected way (semi-automatic). Although it is likely that we will not see milestones in the near future for empowering the model with strong reasoning ability, fortunately we have seen some milestones these years, capable of memorizing and summarizing stuff very well. GPT (Radford et al., 2018) is undoubtedly one of the milestones.

GPT is short for Generative Pre-Training, initially proposed by OpenAI back to 2018 (quite a while ago 😂) for language modeling. In stricter terms, it is called casual language modeling (CLM in order for differentiating it from other language models such as Masked Language Modeling), namely, next word prediction given previous consecutive words in a sequence, which is illustrated below.

Briefly interpreting GPT from its name, generative indicates it is something that is very good at generating stuff. One important element making GPT’s generative ability powerful is that it applies an attention mechanism called masked self-attention mechanism (MSA), The MSA was initially used in the decoder of the transformer architecture from the paper titling “Attention is all you need” (Vaswani et al., 2017). The transformer paper by Google is deemed as a very important work in NLP since it proposed a new network architecture paradigm that completely relies on attention instead of previously commonly-used recurrent architectures such as LSTM for learning sequential data like texts very well. It is important or even transformative (that’s probably why it is called transformer) so that some claims like “LSTM is dead. Long Live Transformers!” went viral in the community. Below I draw a graph hopefully helpful for understanding the self-attention mechanism in the transformer architecture.

For knowing more about the transformer architecture and its self-attention mechanism (what is the intuition behind and why it works so well), here are a number of really helpful tutorials from the Made With ML community. Specifically, for knowing more on GPT, the illustrated GPT-2 blog is a good starting point.

The other part of GPT is pre-training. Pre-training is a very trendy term in transfer learning. What usually appears simultaneously with pre-training is fine-tuning. Basically, transfer learning says training a model beforehand on general dataset to learn some general features from the dataset (pre-training) and then transfers the learnt features to downstream specific tasks (fine-tuning). To gain a broad enough features, the dataset required for pre-training tends to be large scale and thus the pre-training is usually conducted in an unsupervised way. In computer vision, the general dataset for pre-training usually refers to the large-score image dataset - ImageNet and the learnt features are some graphical knowledge such as contours, colors etc. The downstream tasks can be identifying specific objects in an image or adding texts to describe the image, etc. By comparison, in NLP, the large-scale dataset usually refers to the unlabeled internet texts such as Wikipedia, Book Corpus or Common Crawl, etc. For example, BERT (Devlin et al., 2018) is pre-trained on Wikipedia (2,500 million words) and Book Corpus (800 million words). The learnt features in this way of pre-training include some general linguistic knowledge such as syntax or semantics (Rogers et al., 2020) that can be used for language understanding in downstream tasks. For fine-tuning in NLP, the downstream tasks are just all kinds of language tasks, such as, sentence/document classification, sequence labelling, reading comprehension, etc. Figure 4 illustrates the perspective of transfer learning in NLP.

To understand transfer learning in mathematics, the pre-training changes the model’s weights/parameters from random initialization so as to fit well to the defined pre-training tasks (such as language modeling task in NLP) using the large-scale dataset. Fine-tuning then adjusts the weights so as to fits well to a specific task (such as sentiment classification in NLP).

GPT is a good example of transfer learning, it is pre-trained on the internet text through language modeling and can be fine-tuned for downstream tasks. What derives from GPT is GPT-2 that simply is a larger model ($10x$ parameters) trained on more data ($10x$ and more diverse) than GPT. As we know CCT requires a model that can generate codes in a sequential way, GPT-2 is a good option for this task due to its generative attribute and good generative quality. Now we get the GPT-2 hammer in our toolkit. Referring back to Figure 4, since the pre-training is expensive in both memory and time, we fine-tune the model instead of pre-training from scratch. Fortunately, there are many pre-trained weights with different sizes available in the 🤗transformers library (see Figure 1). However, all is ready except for one thing - the downstream dataset, which is introduced in the next section.

2. Dataset Preparation

We know GPT-2 was initially proposed for language understanding through the pre-training on a CLM task. However, we should not limit its application only in language. To put it another way, the reason that it is good at generating coherent paragraphs of text is because it “knows” well to output the next occurrence given the context as the input in a sequence. In CLM, text just fits the pattern where the next occurrence is the next word and the context is the previous words in a sentence (see Figure 3). With this view, it is easy to deduce GPT-2 can be used for tasks involving sequence alike datasets. Image is possible (such as Image-GPT) if we think of an image as nothing but a sequence of numeric pixels. Music is possible if we think of a piece of music as a sequence of notes, such as MuseNet.

It can be easier to understand if we think about GPT-2 or any other deep models from the mathematics perspective. The truth is that they just know numbers and do not know stuff like positions, faces, colors, or words directly. They can know different words indirectly because different words are represented by vectors (nothing but different numbers) before being fed to the models. They know positions because the positions are represented by different numbers before being fed to the models.

Codes can be taken as sequential alike data for sure and thus the CCT can be performed by GPT-2. Below details the process of code dataset preparation for Autocoder.

First, we need to get the codes online. Here we avoid using some existing benchmarking datasets because we want to achieve this CCT from the very beginning stage - dataset mining. For this purpose, there are so many open source libraries that provide large volumes of codes available. As a starting point, let’s just focuses on The Algorithms library now. We want Autocoder to help auto-complete codes at a general level. The codes of The Algorithms suits the need! Also, I think the codes from The Algorithms is well written (high-quality codes!). We want Autocoder to be able to generate both Python and Java codes so we simply clone the corresponding repositories from The Algorithms.

Next, we preprocess the dataset in the way as illustrated below.

We see from the graph that a source code file is split into several examples by applying a slicing window. The slicing window is just used to split the code content in a file into several segments. The segments are referred as the code snippets that we want the GPT-2 model to learn something from and can help auto complete code snippets at testing time. Also, we don’t use the whole file as a code snippet because GPT-2 is sensitive to the input example/sequence length (The self attention mechanism has a quadratic complexity of both memory and time with respect to the sequence length, so a research branch has been working on optimizing this bottleneck, such as, Linformer). Because we used both Python and Java codes as the training set, two special tokens known as control codes, namely, <python> and <java> are added to the GPT2 tokenizer. With the control codes prepended at the start of each example as seen from Figure 5, the model will know which programming language an input example corresponds to. This will also help model make decisions between languages for generating codes accordingly at testing time. The following presents the core codes of how this is implemented in Python.

from transformers import GPT2Tokenizer

#load GPT2Tokenizer from transformers.

#We set do_lower_case=False because programming codes are case sensitive (at least for Python and Java)

gpt2_tok = GPT2Tokenizer.from_pretrained("gpt2", do_lower_case=False)

#add special tokens, namely, the control codes <python> and <java>

special_words_to_add={"additional_special_tokens": ["<python>", "<java>"]}

gpt2_tok.add_special_tokens(special_words_to_add)

#define the stride of the slicing window

stride=10

#define the length of each tokenized segment

segment_len=254

source_code_file="src1.py"

examples=[]

with open(source_code_file, "r", encoding="utf-8") as f:

#read the raw code content

code_content = f.read()

#tokenize the code using GPT2 tokenizer

encoded = gpt2_tok.encode(code_content)

#prepended the special token at the beginning of each input

prepend_control_code = gpt2_tok.encode("<python>") if source_code_file.endswith("py") else gpt2_tok.encode("<java>")

#we also want to append the end_of_sequence_token (eos_token; this is optional)

append_eos=gpt2_tok.eos_token_id

#slicing the code into segements by taking a stride each time

for i in range(len(encoded) // stride):

seg = [prepend_control_code] + encoded[i * stride:i * stride + segment_len] + [append_eos]

examples.append(seg)For the whole script of dataset preparation, go to this script.

3. Finetuning

Before fine-tuning, we split the dataset into a train set and development set at a ratio of $9:1$. This leads to ending up with around $69k$ training examples and $7k$ development examples.

The 🤗transformers library contains the implementation of the GPT2 model with a language modeling head on top (linear layer with weights tied to the input embeddings), named GPT2LMHeadModel in the library. We use it for fine-tuning, where the GPT2 model is initialized by the pre-trained GPT2 weights before fine-tuning. The fine-tuning process trains the GPT2LMHeadModel in a batch size of $4$ per GPU. We set the maximum sequence length to be $256$ due to computational resources restrictions.

Although there are different sized pre-trained variants such as distilgpt2, gpt2-large, gpt2-medium, etc., we select distilgpt2 and gpt2-medium for fine-tuning. Both are fine-tuned on two GPUs (12GB RTX 2080Ti and 8GB RTX 2070 Super) with around $24$ hours for fine-tuning gpt2-medium (approx. $86k$ total steps ) and $8$ hours for distilgpt2 (approx. $69k$ total steps). We use Adam as the optimiser and set the learning rate to be $5e-5$ with warmup ratio $20\%$ of the total training steps. During the fine-tuning, the best model saved is determined by perplexity evaluated on the development set with evaluation step of $200$. For tracking the training process, we use the awesome wandb tool for recording the experimental details. Here logs the training details of fine-tuning distilgpt2 and gpt2-medium for Autocoder. Below plots the state of development loss during fine-tuning from wandb.

hello world

This repository provides the code-level details of Autocoder.

4. Demo and Discussion

With the fine-tuned models, now let’s try some examples for code completion by Autocoder and qualitatively analyze its performance. The examples presented in this section is based on the fine-tuned gpt2-medium version in Python.

The first example is: when I enter def factorial as the prompt code for Autocoder, which I intend to implement a function of calculating the factorial of a number. What Autocoder returns to me is

def factorial(n):

return 1 if n==1 else n*factorial(n-1)Regarding the performance in time, this generation takes around 5 seconds (on a computer equipped with a strong CPU and a RTX 2080 GPU). This may need to be optimized if in a real-life use case. Aside from the temporal performance, this looks a very good-quality generation. However, for now, I take a grain of salt regarding Autocoder’s performance. I want to test it further with such an example: def factorial(m). What Autocoder returns to me is

def factorial(m)->int:

"""

Return the factorial 'm'

>>> import math

>>> all(factorial(i) == math.factorial(i) for i in range(20))

True

...(some nonsense codes)This turns out that only the first line of comment looks good. I have to say this does not go as well as I expected. Autocoder should give me the code snippet the same as the def factorial example except for only changing n to m if it really understands the code. This invokes something I’d like to share.

Does Autocoder reason?

As far as the evidence, it looks that Autocoder generates a nice code snippet for the def factorial example. This is most likely cherry-picked. When I review quickly back to the training source code, there actually exists such a factorial function. If Autocoder fits too much into the training code, it is overfitting or to say it memorizes code rigidly and does not know how to generalize to new situations. This is called a narrow generation ability of a trained deep model as in the literature (Chollet, 2019). In another words, a deep model lack of a broad generalization ability implies it lacks the reasoning ability. For now, Autocoder built upon GPT - a very powerful generative model nowadays, does not gain a reasoning performance near to humans. The def factorial(m) is a piece of evidence to justify this conclusion and the following I give one more example To further support the conclusion.

When I enter def sum as the prompt code, which I intend to implement a function of summing two numbers. However, Autocoder returns to me,

def sum_of_series(num_of_terms:int, power: int) -> float:

"""Calculate Sum of Series.

>>> sum_of_series(1, 1, 10)

55.0

>>> sum_of_series(1, 10, 100)

49600.0

"""

sum = (num_of_terms / 2) * power

return sumAlthough the code makes sense, it is not what I expected. I later figure out the reason that it behaves like this is because there exists such a sum_of_series function instead of the sum(a,b) function in the training set.

What does this tell? I would say that this is a big and important question in the way making AI to human-level intelligence. Although it is not that easy to tackle on the reasoning issue, the good news is that much concern has been raised recently in the community. Also, some seemingly promising work has been done into this direction. For example, Chollet critically discusses the measure of intelligence, which is a nice piece of work to read. And, some insights from the HANS paper (McCoy et al., 2019) that analyzed a language inference task (MNLI, one of GLUE tasks) reveal that the state-of-the-art language understanding models including BERT performs well in MNLI because it summarizes some surface syntactic heuristics well from the training examples. Hence, its performance can go down quickly when making changes to the test set and breaking the heuristics. Similarly, Gardner, et al., 2020 proposed that datasets authors should adding more challenging test examples to the test set (called contrast sets originally) in order to more accurately evaluate a model’s true linguistic capabilities. Although leaderboards usually look overtaken by modern deep models, demonstrating a sense of AI hype, they are more like task-specific tuning. What the future needs is to do more work than this.

How do we learn?

Taking a step back from criticizing Autocoder, let’s quickly recall how humans learn coding, which also applies to learning any other stuff. In analogy, the pre-training of GPT-2 is like our language learning in school in the past. The fine-tuning of GPT-2 for Autocoder is like we step into university and select a programming module for learning how to code. Autocoder at inference time is like we sit in the exam room for testing how well we learn from the past and the programming module. I’d like to say humans will achieve a better score than Autocoder at 100% percent (maybe not sometimes😂) if they go through all materials of the programming module (like Autocoder is trained through epochs of iterations of the training set). Then what is the problem?

First, let’s leave alone the topic of if it is possible to achieve AGI. Let’s just hypothesize for now it is possible to approximate a machine to a human. With this premise, we learn something from the narrative. The key difference in the learning of humans and Autocoder is that we learn not just language stuff from schools. We also learn visual objects, physical interactions, emotional relationships, etc. This says that we have some common knowledge or common sense on the world. For example, we comprehend Pythagorean theorem most likely because our teachers once drew three lines on the blackboard as the visual aids to help us understand it when we were young. And we understand the lines because we can associate it to the physical world’s concepts such as distances. Through all the way of our learning journey, we form a big network that contains a knowledge graph, basically, mirroring our understanding on the world. With knowledge accumulated, we become versed at organizing and associating the nodes in the knowledge graph. When we come to perform a new task even though it is a brand new task we have never tried before such as driving a car under a dark tunnel, we know how to take actions to minimize the possibly-induced damage based on our prior knowledge. That’s the strength of human-level generalization and reasoning through prior experience. To empower machines with this strength, the intuitions behind human learning is instructive for future work made into machine learning.

5. Future Work

As presented, now Autocoder is very basic, only serving as the starting point of more work into it. The following summarizes a list of future work for Autocoder.

- Expand the dataset (and construct the dataset more carefully) and increase context window. Try larger generative models like GPT-2 large or even GPT-3 variants as proposed recently if the computational resources are allowed.

- Remove overlapping between training examples and dev examples for contamination studies. That says, to what extent the model memorizes examples rigidly or at surface heuristics level during training.

- Try some adversarial examples (more complicated for model’s reasoning capability testing purpose) to test the robustness of the model.

- Integrate this into real-life use case such as a code editor - Sublime Text, where a threshold of joint probability may need to be studied for code snippet recommendations.

- Try some ideas of location-aware code generation. For example, if a human coder is sitting writing a comment, the Autocoder should be aware of the coder’s context (left and right if available) to help complete the corresponding content.

- Model size and inference efficiency is a problem in real-life use cases.

- Do research in this problem domain to grab a general idea of what work has done in the literature for this particular problem.

More resources.

- The video inspiring the project

- Some commercial products leveraging GPT-2 for auto code completion

- Related Paper - Code Generation as a Dual Task of Code Summarization

Disclaimer: The introduction to Autocoder is by no means showing it generates codes with a good sense of reasoning. More of this blog’s purpose is to introduce the state-of-the-art generative model GPT-2 and present an example of how it is used for code completion.

Last, thanks to JiaZheng who kindly provided the computation resources for making this blog possible.

If you have any thoughts you’d like to share with me about the blog, send me an email via wangcongcongcc@gmail.com or you are welcome to talk with me on my Twitter.